When one thinks about animal abuse, the most egregious acts often come to mind—brutality, neglect, and emotional trauma inflicted through overtly harmful behaviors. However, a more nuanced question arises: is making a dog uncomfortable a form of abuse? This inquiry invites exploration into the complex dynamics of canine welfare, behavior, and the psychological ramifications of human-dog interactions.

The understanding of animal welfare hinges on both physical and psychological dimensions. Dogs, as sentient beings, experience discomfort not only through physical means but also through emotional and environmental stressors. This leads to the concept of discomfort, which can be both overt and subtle. To assess whether making a dog uncomfortable constitutes abuse, it is essential to dissect the implications of discomfort and how it relates to the broader notions of ethical treatment.

Discomfort in dogs can manifest in various forms. It may be as blatant as physical restraint or as insidious as forcing a dog into a situation that triggers anxiety or fear, such as loud noises or interactions with unfamiliar people. The juxtaposition of discomfort and abuse necessitates an exploration of intent and consequence. Does the act of making a dog uncomfortable stem from a place of ignorance, or is it a result of deliberate cruelty?

In instances where discomfort arises from well-intended but misguided activities, such as clumsy training methods or inappropriate socialization practices, the intent may not align with malice. Nevertheless, the outcome remains significant. A dog may visibly display signs of stress, including pacing, excessive panting, or avoidance behavior. These indicators compel the observer to question whether such actions serve the dog’s well-being or contribute to a detrimental experience.

Conversely, when making a dog uncomfortable is steeped in malicious intent—punishing a dog for behavior that is a natural expression of its instincts or failing to recognize the individual needs of a dog—this approach not only borders on abusive but can leave long-lasting psychological scars. The impact of these experiences can erode trust, leading to behavioral issues and a fractured human-animal bond.

A significant aspect of this discussion concerns the concept of learned helplessness. When a dog is repeatedly subjected to uncomfortable situations without an avenue for escape or relief, it may eventually become desensitized and resign to its fate. This psychological state, where a dog loses the will to act, is closely associated with abuse, albeit in a subtler form. Is it not abuse when a dog’s spirit is quelled, even if the practitioner believes they are simply asserting authority or discipline?

Moreover, societal norms and cultural perceptions play pivotal roles in determining what is considered acceptable treatment of dogs. Practices that were once deemed acceptable—such as physical corrections in training—are increasingly recognized as harmful. The evolution of our understanding of canine behavior has led to more compassionate training methods that prioritize positive reinforcement rather than discomfort as a means of behavior modification.

Yet, the challenge remains. How do we delineate between necessary discomfort that fosters growth, such as exposure to new experiences, and unnecessary discomfort that leads to distress? For example, socialization is essential for a dog’s development, involving exposure to new environments, other dogs, and varying stimuli. However, if this exposure is not calibrated to the dog’s comfort level, it could lead to extreme fear or anxiety. Striking a balance requires a nuanced understanding of canine behaviors and signals that inform the handler when a dog is grappling with discomfort.

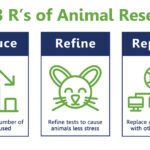

As advocates for animal welfare, it is incumbent upon us to foster an environment where canine discomfort is minimized. A proactive approach involves rigorous education about dog behavior and body language, allowing caretakers to recognize signs of distress. This shift in perspective does not merely advocate for the elimination of discomfort but rather promotes an empathetic understanding of when discomfort is truly helpful versus when it is harmful.

Furthermore, this discussion raises ethical dilemmas for dog trainers and caregivers. Is one justified in pushing a dog beyond its comfort zone for the sake of training? While the urge to promote resilience and adaptability is noble, the crux lies in ensuring that such methods are employed judiciously. Professional trainers must be vigilant about recognizing individual thresholds and adapting their approaches accordingly to avoid contributing to a cycle of discomfort and mistrust.

Ultimately, to answer the question, “Is making a dog uncomfortable a form of abuse?” one must consider the context, the intent, and the outcomes of such interactions. An act is not simply defined by its surface-level actions but by the ripple effects it causes in the life of a sentient being. As we continue our advocacy for these loyal companions, it is crucial to challenge outdated norms and create a society where discomfort, when it arises, is systematically acknowledged, analyzed, and addressed with compassion. Treating discomfort as an indicator rather than an inevitability can help foster a future where every dog lives not only free from abuse but thrives in an environment of empathetic understanding and care.