In the ongoing discourse about animal welfare, tail docking in dogs emerges as a contentious practice that oscillates between tradition and perceived cruelty. Historically, tail docking has been carried out for various reasons, including aesthetic preferences, historical utility, and misguided notions of health. As societal values evolve towards a more compassionate understanding of animal well-being, one must ponder whether this entrenched practice can be justified in light of modern ethics.

Tail docking, the surgical removal of a portion of a dog’s tail, has its roots deeply embedded in the annals of canine history. The practice can be traced back to ancient civilizations, where it was ostensibly performed to prevent injury in working dogs, especially those involved in hunting or herding. Advocates of tail docking posit that a shorter tail could reduce the risk of accidents, particularly in aggressive encounters or when weaving through underbrush. Yet, this rationale is steeped in speculation rather than empirical evidence.

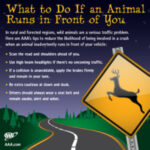

Contrarily, the contemporary understanding of canine behavior and anatomy suggests that tails serve critical functions for dogs. The tail is not merely an appendage; it is an essential element of canine communication and balance. Through the movement of their tails, dogs convey emotions, from happiness to aggression. Moreover, the tail plays a vital role in maintaining equilibrium during movement, essential for a dog’s agility and coordination. Its removal thus impedes these natural behaviors, potentially leading to confusion and behavioral issues.

As we delve deeper into this topic, the ethical implications of tail docking become clearer. The procedure is performed without anesthesia in many regions, causing undue suffering and trauma to the animal. Advocates for animal rights argue that inflicting pain for the sake of tradition undermines the evolution of our moral accountability toward animals. The simple act of removing a tail can have lasting repercussions, both physically and psychologically, challenging the justification for such an invasive procedure.

Various veterinary organizations and animal rights groups now campaign against tail docking, urging a shift towards more humane alternatives. The American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) and the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons (RCVS) have openly criticized the practice, emphasizing that there exist no valid medical reasons for routinely docking tails in dogs. The global pulse is shifting, with countries like the United Kingdom implementing bans on cosmetic procedures like tail docking, reflecting a growing consensus that animal welfare should supersede ancestral customs.

Opponents of the ban often cite breed standards established by kennel clubs as a justification for tail docking. Certain breeds, such as Doberman Pinschers and Boxers, have historically been showcased with docked tails in conformity with these standards. This desire for adherence to tradition can create a paradox: prioritizing aesthetics over well-being. The question arises: Do breed standards serve the interests of the dog, or do they merely perpetuate an antiquated norm? A comprehensive reevaluation of breed standards may be necessary to align them with modern views of animal welfare.

Additionally, public awareness of animal suffering has burgeoned in recent years, and with it, a growing demand for ethical treatment of pets. Awareness campaigns, educational initiatives, and a general societal shift towards compassionate practices beckon a new era for pet care. An increasing number of dog owners are now seeking out veterinarians who adhere to these standards, favoring practices that prioritize the physiological and psychological health of their dogs over mere appearances. Hence, the prospect of transformation looms on the horizon, propelled by a more educated populace.

Despite the mounting pressure to abandon the practice, resistant attitudes linger within specific circles of dog breeding and ownership. Some proponents argue that tail docking can prevent specific health issues—claims that are often unsupported by scientific studies. This resistance highlights the need for robust dialogue between opposing factions, fostering an environment where change can be realized in a balanced and researched manner.

Moreover, one must consider the anthropological aspect of tail docking. Canines are our companions, yet they are still regulated by standards that echo human desires more than canine needs. The struggle against tail docking encapsulates the broader conflict between tradition and progress. The moment we begin to prioritize the welfare of our pets over age-old customs, we take significant strides towards a more humane and ethical treatment of animals.

In addressing tail docking, it’s imperative to promote open discourse rather than engender hostility between supporters and opponents. Education plays a pivotal role in dismantling myths and fostering understanding. By enlightening dog owners about the physiological advantages of retaining a tail, we can motivate a shift towards an inclusive approach to pet care that respects the innate characteristics of dogs as sentient beings.

In conclusion, while tail docking may have historical roots, its justification in the context of modern dog ownership is increasingly tenuous. As knowledge expands and societal values shift, the ethics surrounding animal treatment necessitate that we reconsider the implications of our choices regarding pet care. Ultimately, the question of whether tail docking is tradition or cruelty rests upon our willingness to challenge ingrained beliefs and embrace a more compassionate future for our canine companions.