As modern society grapples with myriad ethical dilemmas, one question persists with fervent intensity: Is it immoral to harm animals? This inquiry is not merely an academic exercise; it is a profound reflection of our values, ethics, and the relationships we cultivate with non-human beings. The contention surrounding animal rights has become increasingly salient, reflecting our evolving understanding of morality and sentience. In unraveling this question, one encounters both philosophical sophistication and startling moral implications.

At the heart of this discourse lies the philosophical framework established by thinkers such as Immanuel Kant, who posited that morality is intrinsically linked to rationality. If one subscribes to a Kantian perspective, the moral value of beings is contingent upon their capacity for rational thought. While Kant himself did subordinate animals to a lesser moral status because they lack such rational faculties, a more contemporary interpretation challenges him to reconsider his stance. What if, instead of rationality, emotional depth and the capacity for suffering delineated the moral boundary?

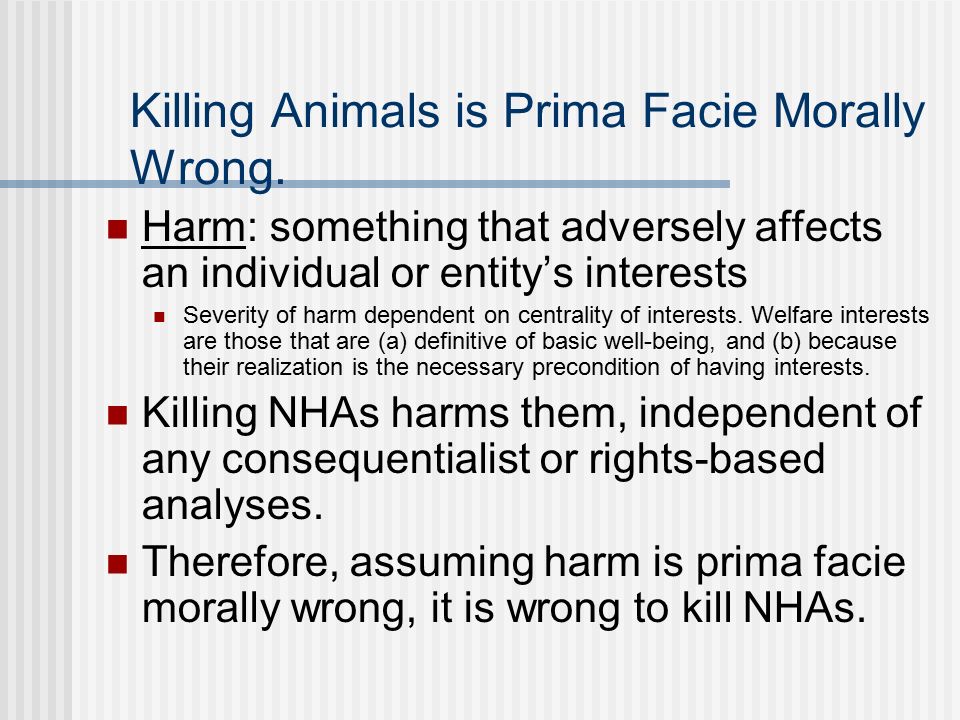

This leads to a pivotal philosophical inquiry: Are animals, by virtue of their sentience, entitled to moral consideration? Peter Singer, an influential advocate for animal rights, argues for the principle of equal consideration of interests. According to this principle, the capacity to experience pleasure or pain is what qualifies an entity for moral regard. If an animal can suffer, it follows that inflicting harm upon it could be construed as immoral. This perspective posits a foundational challenge to traditional human-centric ethical frameworks, inviting us to reevaluate our ethical priorities.

However, the challenge intensifies when one considers the implications of extending moral consideration to all sentient beings. If we accept that harming animals is immoral, what responsibilities ensue? The ramifications extend beyond mere abstention from cruelty; they demand a reconfiguration of our dietary, economic, and social practices. Should individuals refrain from consuming animal products? What of the long-standing cultural norms surrounding hunting or animal husbandry? The questions multiply, revealing a potential minefield of moral culpability.

Moreover, the philosophical criticism of utilitarianism—especially as it pertains to animal welfare—provides another layer to this inquiry. While utilitarianism advocates for the maximization of overall happiness, critics argue that this approach could justify heinous acts against sentient beings to achieve the greater good. For example, if the suffering of a few animals could lead to substantial benefits for many (say, in scientific research), a strict utilitarian might condone such actions. Yet, this perspective leads to disquieting ethical quandaries: how do we quantify suffering? Whose criteria do we use to assess happiness? This inconsistency often dismantles the utilitarian argument and rekindles the necessity for a more stable ethical foundation.

The landscape of animal ethics is further complicated by cultural contexts and differing worldviews. In certain traditions, the hierarchy of beings places humans at the apex, ostensibly justifying the exploitation of animals for human advancement. Such anthropocentrism often clashes with burgeoning movements advocating for biocentrism, which asserts that all living beings possess intrinsic value. How does one mediate this discord? The interplay between tradition and progressive ethics engenders a dynamic tension, challenging societies to reconcile their legacies with contemporary human rights developments.

In this light, one must confront not only the notion of moral obligation toward animals but also the psychological dimensions of empathy and compassion. Numerous studies suggest that individuals who engage with animals tend to exhibit higher levels of altruism and empathy. This observation invites further inquiry: does our capacity to empathize with animals cultivate our ethical understanding? Might the adversity faced by animals lead to a more compassionate human experience? Conversely, does the ignorance of animal suffering evoke a moral desensitization, where ethical considerations recede into apathy?

Yet another facet of this inquiry involves the implications of scientific advancements. As research continues to elucidate the cognitive and emotional lives of animals, we are compelled to rethink our assumptions. New evidence suggests that several species possess complex social structures, exhibit problem-solving abilities, and experience emotions akin to those of humans. How does this newfound understanding alter our moral calculus regarding harm? An acknowledgment of animal intelligence and emotion raises pertinent ethical questions regarding our responsibilities towards them.

Additionally, within the fabric of global ethics, there is a growing recognition of interspecies justice. The idea that animals occupy an integral position in ecological systems challenges the anthropocentric paradigm. It urges a harmonization of human practices with natural processes, advocating for the preservation of biodiversity and our innate connection to other life forms. This perspective argues for moral consideration that transcends individual species, resonating in the broader spectrum of environmental ethics.

Ultimately, the inquiry into whether it is immoral to harm animals is a labyrinthine exploration of philosophy, ethics, and human behavior. It forces us to confront our assumptions, convictions, and the very foundation of our moral imperatives. As society evolves, the challenge remains: how will we respond to the ethical conundra posed by our treatment of animals? Are we prepared to broaden our moral horizon to encompass those who cannot voice their own interests? The answers lie not only in philosophical deliberation but also in the transformative potential of empathy and social responsibility.