As culture shifts and societal norms evolve, the question of deer hunting and its classification as animal cruelty surfaces with increasing frequency. This discourse is not merely about whether hunters should continue their practices unimpeded; it probes into the broader ethical implications of our relationship with wildlife and the moral weight of taking a life for sport. Understanding the layers beneath this discussion requires a multifaceted exploration of humanity’s history with hunting, the regulatory frameworks that govern it, and the psychological dimensions that drive individuals to engage in such activities.

Historically, hunting has been interwoven into the fabric of human survival. For millennia, the act of hunting was necessitated by the primal need for sustenance. Ancient societies depended on deer and other game not only for food but also for clothing and tools. This survival instinct has evolved into modern recreational hunting, which often raises eyebrows and incites fervent debate about its morality. The distinction between subsistence and sport is crucial here: while survival hunting may still hold some ethical justification, recreational hunts can be perceived as superfluous, even cruel.

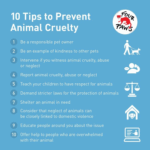

At the heart of the debate lies the concept of animal cruelty. Defined broadly, animal cruelty refers to inflicting suffering on animals, which, according to various animal welfare organizations, certainly encompasses acts that result in undue pain, distress, or cause long-term harm. Critics of hunting argue that the very act of pursuing an innocent creature with lethal intent constitutes a cruel deprivation of its life—a sentiment echoed in discussions surrounding animal rights. The premise of inflicting suffering—regardless of its intent—often leads to visceral reactions, particularly when considering the widely accepted tenet that animals are sentient beings capable of experiencing pain.

Opponents of deer hunting assert that this sport is predicated on a fundamental misunderstanding of the complexities of wildlife biology and ecology. While proponents argue that regulated hunting can help manage deer populations and prevent overpopulation, the efficacy of this argument is often questioned. Ecological systems are intricate webs of interdependence, and the introduction of hunting as a supposed corrective measure can yield unintended consequences, such as balancing other species’ populations or disrupting natural predator-prey dynamics. Therefore, the argument of necessity becomes fraught with potential moral pitfalls.

Moreover, the fascination surrounding hunting illuminates deeper sociopsychological motivations. It is essential to ponder why individuals feel compelled to partake in something that can be construed as inhumane. For many hunters, the allure lies in the thrill of the chase—the excitement, the camaraderie, and the visceral connection to nature that hunting provides. These individuals often revel in the challenge, deriving satisfaction from not just the act of hunting, but also the skills and precision it entails. Yet, this fascination often clouds a critical evaluation of the impact on the hunted and raises questions surrounding empathy and respect for life.

The contrast between the idealized version of hunting as a noble pastime and the visceral reality of killing serves as a point of contention. Many hunters advocate for the philosophy of ethical hunting, emphasizing principles such as conservation and respect for the animal being hunted. They argue that by participating in regulated hunting, they contribute to conservation efforts, funding wildlife preserves and ensuring sustainable animal populations. Nevertheless, this rationale does not eliminate the underlying moral ambiguity of deriving pleasure from the death of an animal, which many see as fundamentally ethical contradiction.

One particularly poignant observation is the experience of the hunted deer itself. Witnessing a fellow creature, possibly terrified, as it is pursued and ultimately killed serves to highlight the emotional and psychological ramifications involved. The process, from the chase to the final demise, invariably disrupts the life of the deer and carries implications that extend into the wider ecosystem. Life is precious, and even if it is deemed necessary for population control, the perspective of the animal remains critical in discussions about cruelty.

Furthermore, the psychological impact on hunters cannot be dismissed. A complex tapestry of emotions accompanies the act of killing, ranging from elation to guilt and everything in between. Many hunters describe a deep reverence for their prey, a conflicting relationship that generates both pride and remorse. It raises a pivotal question: can one truly respect an animal while simultaneously ending its life for sport? The ethical dilemma spurs further inquiry into the hunting culture itself—does it cultivate respect for nature, or does it risk commodifying life, reducing animals to mere trophies?

In evaluating whether deer hunting should be classified as animal cruelty, it becomes vital to recognize that the answer may not be entirely binary. There exists a spectrum of opinions that ranges from outright condemnation to rational acceptance based on conservation arguments. However, balancing conservation needs with ethical treatment of animals remains a daunting challenge. Society must strive to foster a discourse that respects both wildlife ecology and the moral obligation to treat living beings with dignity.

Ultimately, introspection is required. If we believe in a world that upholds justice and compassion, then the classification of deer hunting as animal cruelty necessitates a thorough examination of motivations, consequences, and the emotional landscapes that inform our choices. Reevaluating our relationship with deer, and wildlife in general, may very well shape the future trajectory of hunting practices and animal rights advocacy alike. It forces us to confront uncomfortable truths about our own nature replete with complexities that cannot be easily categorized.