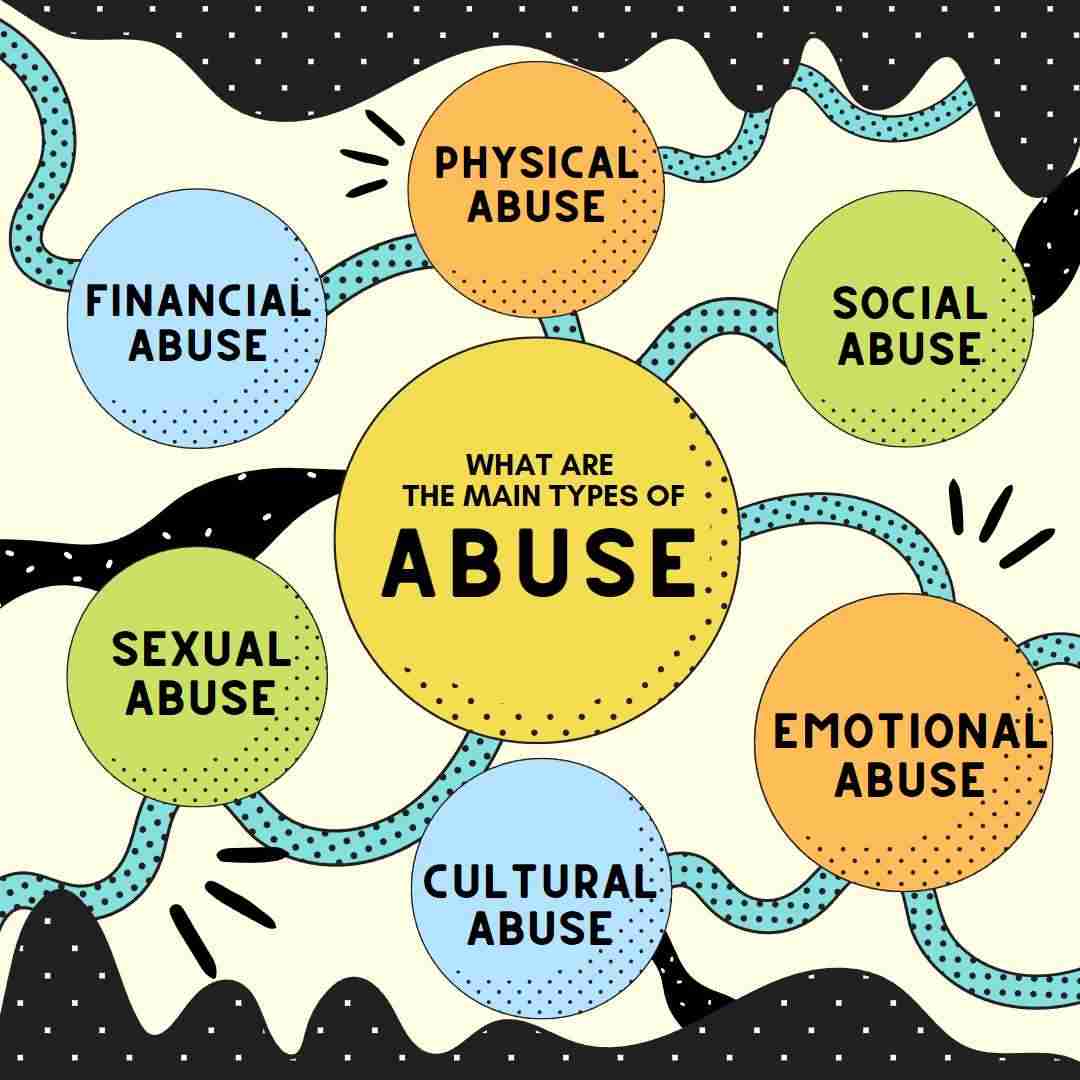

When we think about animal abuse, a plethora of images may flood our minds—abandoned pets, mistreated farm animals, or neglected wildlife. However, there exists a disconcerting reality where certain actions toward animals, often overlooked, escape the rigorous scrutiny typically associated with abuse. What constitutes abuse is often a nebulous concept, shaped by cultural paradigms, legislative frameworks, and societal norms that can vary significantly from one region to another. Thus, a pressing question arises: what practices should be considered abusive—but presently aren’t?

First and foremost, let’s scrutinize the concept of “production line” existence bestowed upon domesticated animals, particularly in industrial farming. In many nations, animals raised for consumption are subjected to conditions that, while compliant with existing laws, raise ethical red flags. These include overcrowded living environments, lack of social interaction, and the absence of natural behaviors that feed their innate instincts. Do we truly believe that these conditions are humane simply because they fall within the established regulatory framework? Or are we overlooking a fundamental aspect of animal welfare—emotional and psychological well-being?

This brings us to the crucial intersection of mental health and animal welfare. Recent studies indicate that many species experience stress akin to human anxiety disorders. Yet, despite this mounting evidence, the mere fact that an animal appears physically healthy is often deemed sufficient clearance for their welfare status. Herein lies a paradox: why do we neglect the psychological torment inflicted upon farmed animals who are unable to exhibit natural behaviors or social interactions? Animals raised in confinement often display signs of distress, depression, and stereotypies, such as pacing or feather plucking. Should these conditions not merit our concern?

Moreover, when we shift our focus from the farm to the household, the issue broadens even further. According to the conventional understanding, abuse is overt and evident—such as acts of physical violence or flagrant neglect. However, what about the subtler forms of trauma that our companion animals endure? Consider the animals subjected to chronic neglect disguised as “busy lifestyles.” While many may argue that simply providing food, water, and shelter suffices, what about the emotional neglect? Can a pet thrive in an environment where it is largely ignored, deprived of companionship and mental stimulation? Should not the transparency of emotional neglect be weighed equally against the blatant disregard of physical needs?

The challenges extend to a more insidious realm—animals used for entertainment or companionship in ways that strip them of their dignity. Zoos and aquariums, despite often presenting themselves as educational institutions, can perpetuate forms of subtle animal abuse. These environments frequently prioritize human entertainment over the psychological wellbeing of the animals. For example, the psychological toll on cetaceans subjected to captivity can culminate in behavioral abnormalities and early mortality—a matter often overlooked when we evaluate their living standards based solely on space and food availability. This raises a compelling question about the ethics of using animals for amusement—should it remain socially acceptable to exploit animals for our enjoyment, despite the emotional scars that may withstand such practices?

Similarly, consider the burgeoning trend of pet breeding, particularly the practice of producing designer breeds. The focus on superficial attributes often eclipses the inherent health issues that breed popularity can spawn. For example, certain dogs bred for specific physical traits might suffer from debilitating hereditary conditions. Shouldn’t the potential suffering imposed by such breeding practices—characterized by an obsession for aesthetics over ability—be classified as a form of abuse? If we deliberate on the emotional and physical ramifications of these breeding choices, our understanding of abuse may need reevaluation.

Another poignant area that eludes conventional definitions of abuse relates to wildlife and habitat. The continuing encroachment on natural habitats for urbanization is a tacit form of violence against wild animal populations. Fragmentation of habitats results not only in loss of biodiversity but also forces wildlife into conflict with human developments. When forced into “unfamiliar” territories, animals often exhibit aggressive or erratic behavior as a means of survival. If we consider the plight of animals displaced from their natural ecosystems, don’t we then bear a moral responsibility to address the ramifications of our expansions? Isn’t the degradation of their habitats a mild form of abuse rooted in human selfishness?

Ultimately, revamping our definition of animal abuse entails a holistic examination of the myriad ways in which animals experience suffering. It might also provoke unyielding discomfort, pushing us to confront the disjointed relationship we share with non-human beings. A broader understanding that encompasses psychological distress, social needs, and habitat integrity may not only redefine what constitutes animal abuse but may also direct our efforts towards more compassionate and responsible care of all living beings.

As we challenge these preconceptions, it becomes increasingly evident that our societal attitudes toward animals need transformation. Perhaps the greatest verdict lies not in legislative changes, but in the evolving conscience of the global community. By recognizing and advocating for those forms of abuse that have long lingered in the shadows of our culture, we can take the first steps toward a future where all animals are afforded the respect and care they inherently deserve.