Throughout the corridors of human civilization, pets have occupied a peculiar place—somewhere between beloved companions and mere possessions. Despite their sentience, individuality, and emotional complexity, the legal framework in many jurisdictions categorizes pets as property. This classification raises profound questions about their treatment, rights, and the ethical implications of viewing them strictly through a property lens. Understanding why pets continue to be labeled as property under the law involves delving into historical precedents, cultural sentiments, and the implications of such a categorization.

Historically, the legal definition of property has been rooted in the notions of ownership, control, and exchange. Just as land, artifacts, and even intellectual property can be bought and sold, the law affords pets a similar status. This analogy, while seemingly straightforward, falters when one considers the nuanced realities of animal behavior and the emotional bonds they share with humans. Indeed, pets are not inanimate objects; they are living beings capable of forming attachments, experiencing joy, and suffering from trauma.

To comprehend the enduring classification of pets as property, one must explore the legal doctrines that underpin this categorization. The historical legacy of animal law stems from an era when animals were primarily viewed as tools or commodities in agricultural and industrial contexts. With the advent of domestication, pets gradually came to be seen as companions, yet the law has been slow to adapt this perspective into its definitions. Thus, even within the realm of modern legal systems, pets often find themselves trapped in an antiquated framework that fails to recognize their inherent value beyond mere ownership.

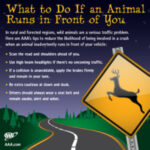

The dichotomy becomes more pronounced as one examines the societal norms surrounding animal welfare. While many people advocate for stronger protections for pets, the legal classification as property complicates these efforts. In cases of divorce, custody disputes frequently arise not about the emotional welfare of the pet, but rather over who has ownership rights. Judges often rely on property laws to determine custody, equating pets to possessions, rather than considering their needs and emotional comfort during unsettling transitions.

Furthermore, moving beyond the personal sphere, the economic implications of pets as property are significant. The pet industry is a multi-billion-dollar sector, with millions of pets considered valuable assets. This perception elevates the status of pets in economic terms yet diminishes their recognition as sentient beings deserving of rights and protections. The more deeply society commodifies animals, the further entrenched the legal definition of pets as property becomes. This creates a paradox where pets are simultaneously cherished and objectified, complicating the dialogue on ethical treatment.

Exploring cultural variations sheds light on alternative models of understanding pets. In some societies, animals are revered within frameworks that emphasize kinship and interdependence rather than ownership. Indigenous perspectives often acknowledge animals as relatives or partners in the shared ecosystem, which fosters a protective ethos comes from respect rather than control. Such views challenge conventional property-based frameworks, advocating for a relational understanding that promotes the welfare of animals beyond transactional dynamics.

Moreover, in contemporary discourse, the emerging field of animal rights seeks to redraw the boundaries of how society perceives and interacts with pets. Advocates argue for legal reforms that would recognize the individual rights of animals, pushing for laws that would allow pets to be considered sentient beings with specific entitlements. This notion gains traction as knowledge around animal cognition and emotional capacity broadens. Science increasingly emphasizes that many animals experience complex emotions akin to human experiences, reinforcing the argument against property-based classifications.

Yet, the journey toward reframing pets as something other than property is fraught with challenges. Legal reforms are slow to materialize, often hindered by deeply ingrained societal beliefs regarding ownership and control. As legislators and jurists wrestle with these progressive ideals, the status quo remains: pets are often viewed as commodities to be owned, traded, or discarded in the unfortunate circumstances of abandonment or abuse.

Toward a feasible solution, a hybrid legal status could be postulated—one that acknowledges pets as more than property yet does not elevate them to the full rights of human beings. Such a classification could ensure that pets are entitled to protections that safeguard their well-being while preserving the crucial bonds they share with their human counterparts. By recognizing the emotional and psychological dimensions of our relationships with pets, society can begin to forge a path toward a more humane legal framework.

In conclusion, the designation of pets as property under the law reflects a historical reluctance to embrace the evolving relationship between humans and animals. This outdated perspective has significant implications, not only for animal welfare but also for the legal systems that dictate and define these relationships. A shift in understanding—from pets as owned objects to companions deserving of respect and protection—can reshape the fabric of societal attitudes toward animals. As we navigate these complexities, it is imperative to advocate for a legal landscape that honors the unique emotional tapestry woven between humans and their pets, transcending the antiquated confines of property law.